|

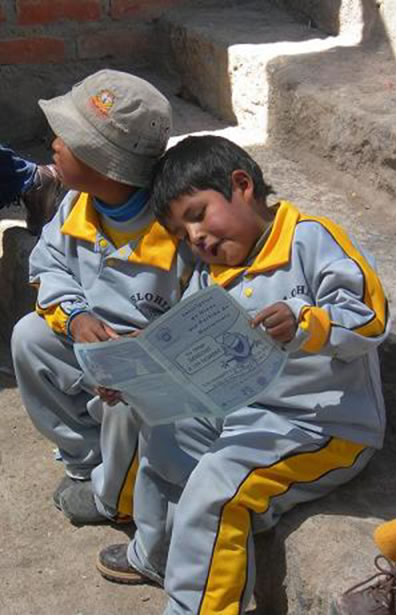

| Valdet Tairi (Macedonia), Audrey Henderson (United States) Carolina Villar (Brazil) – at the farewell party for Helsinki Summer School participants at The Club in downtown Helsinki. |

I knew as soon as I stepped onto the marshy patch of ground that I was in trouble. I can’t fall down. I just can’t fall down. I commanded myself silently. PLOP! Fortunately, the saturated grass provided a soft landing, so the only injury I suffered was to my pride.

“Let me help you,” said Mihai, one of my classmates, chivalrously extending his hand.

“I’m fine,” was my brusque response. I was determined not to let my advanced age betray me as incapable of navigating the course with everyone else. I righted myself, and had A-L-M-O-S-T regained my bearings, when PLOP! I found myself on the ground again.

“Audrey, let me help you,” Mihai insisted. “You fell down a sinkhole.”

I looked down to find that it was indeed true. So I wasn’t just an infirm old lady who couldn’t manage an ordinary outdoor field hike. I also had not been the only one to have fallen victim to the same fault in the ground.

So I was helped to my feet, continued to navigate the soggy grass, and fortunately, did not fall again. The day was highlighted by a fresh air picnic for lunch, and after the fastest shower of my life, followed by a bus and tram trip into downtown with a classmate assigned to the flat down the hall, a homemade, authentic Italian dinner (prepared by two Italian classmates!) at my instructor’s cozy flat.

This was but one of several field trips undertaken by my class, entitled Planning a Growing Urban Region, one of a dozen held during August 2007 as part of the Helsinki Summer School program. The program is an international summer study intensive, conducted in English and targeted toward graduate level students, with a few advanced undergraduates and professionals sprinkled in for variety. Our class was conducted by the Network for Urban Studies, a cooperative of the University of Helsinki and the Helsinki University of Technology.

The Helsinki Summer School Program

The Helsinki Summer School program began in 2000 as the contribution of the University of Helsinki to the European City of Culture project. From 2001 to 2004 the program was administered by a consortium of nine universities of Helsinki area (listed below). After an evaluation in 2004, the program was reorganized with a new administrative model and outsourcing service with the nine participating universities.

In 2007, more than 300 students from 50+ countries around the world were enrolled in a dozen courses included in the program, with course credits issued in ECTS (European Credit Transfer System) generally varying from 4 to 8 units per course. Most were in their 20s, with a few in their 30s. Then there was me, the grand old lady of the program, although I was to learn later that there was another participant even older than I, although we never met.

Although the course in which I had enrolled was directly related to my work in community development and research in housing related issues, and was only a short-term intensive program, the cost represented a severe strain on my finances, as I received no assistance whatsoever. The program did offer scholarship funds, but an application would have required a recommendation from my advisor, which I knew would hardly be forthcoming, as I had not been in residence for several years.

Seizing the Opportunity

I also felt painfully self-conscious about my age. At several points before I actually boarded the plane, I questioned the wisdom of my decision to take on a study abroad program in my 40s. At 47, I knew I would be older than most of the other participants, and steeled myself for that. I was not prepared, however, to discover on the first day of class that I was even older than the main course instructor! Had I been aware of this fact before my arrival in Helsinki, I might very well have decided not to make the trip after all.

The opportunity for study abroad had not been available when I was younger. In high school, as an undergraduate, and even in my earlier years as a graduate student, there was simply no money in the budget for such “frivolities” as study abroad. In the past, I had told myself that I would undertake study abroad “later,” and when “later” finally arrived; I decided that I was too old.

However, a profound loss earlier in the year sealed my decision to finally pursue what had been nearly a lifelong desire to experience life outside my own culture, at least for a short period. On of my very best friends, someone I had known since I was a teenager, had been suddenly struck down and died from Lymphoma aged only 48 years. The shock removed the cliché from the realization that life could be taken from us literally at any time.

Although my friend was taken much too soon, he had at least had the opportunity to realize most of his life’s desires and ambitions. I, on the other hand, had not. So I was determined to follow through with this, no matter what, and that was that.

I wasn’t particular about where I went. I did, however, have a number of constraints which limited my options, finances being the overriding consideration. I could neither afford nor justify a long-term program. Language was another limitation. Although I speak and write reasonably well in French, I had not studied the language for two years, and as a result I did not feel confident in my abilities to take on coursework in French. I also hoped to find a program which provided accommodations for its participants. Finally, I was hesitant to undergo a series of immunizations or a visa application–again because I was taking on this endeavor on my own, and did not want to make a critical misstep which would come back to haunt me.

I had learned about the Helsinki Summer School program some years earlier from an acquaintance who had emigrated to Finland from Germany. He had not attended the program himself, but was aware of it, and mentioned it as an option when I had made an offhand comment about my desire to study abroad.

The loss of my friend had triggered the recollection, and I decided to investigate. I began by examining the Helsinki Summer School website, which proved to be a rich resource not only about the program, but about Helsinki as well. I learned more through email inquiries to the staff. The program proved to be made to order for my needs and preferences. I submitted my application and was accepted. I also received an assignment in an efficiency flat in a section of Helsinki called Pihlajamäki which was private, as well as less expensive than the shared-room hostel accommodations downtown. This choice proved to be significant–as I truly became a resident, rather than a visitor, for the duration of my stay in Helsinki.

Academically, I was well prepared. The reading and the course requirements were challenging, and the schedule was rigorous, running the equivalent of a full work day, five days per week, with a break for lunch. Still, there was nothing involved that I could not handle, having executed all the stages of a rigorous graduate program up to and including completing a draft of a doctoral thesis.

I was also gratified to see that I was not the only participant in the program with dark skin. In retrospect I should have realized that particular fear had been groundless. Although there are not many black people in Finland, Somali émigrés and refugees actually comprise one of the larger group of immigrants to Finland. In and around Helsinki especially, I was but one of a diverse mixture of residents and visitors, and never encountered an incident of racism.

As a woman, I also felt secure traveling alone and after dark, although in early August especially, dark does not come before 10 or 11 p.m. local time. Of course, as in any urban area, it is wise to keep one’s wits about oneself. Still, Helsinki is a very safe city, including public transit, which is clean, fast and punctual.

Socially, however, I was completely at sea. Although I am told that I look younger than my years, I do have visible gray hair, and I felt inhibited in making overtures to my much younger counterparts, especially the men. I did not want to be perceived as forcing anyone to humor the weird old lady when my company really wasn’t desired. I especially didn’t want to give the impression of making unwanted romantic overtures. One of my few regrets was that I allowed these self limiting attitudes to put a damper on my extracting the full measure of the rewards to be gained from the experience.

For instance, I sat out a number of the social activities, simply because I convinced myself I would be conspicuously out of place. Granted, many of the programs were geared toward the typical study abroad participant of conventional college or graduate student age. However, many others were not.

For their part, my instructor, my fellow classmates, the program staff and even participants from other courses, were nothing but welcoming. I was never made to feel out of place. That notion was generated strictly within myself. Fortunately I did manage to participate in a number of the social diversions offered, and enjoyed each of them tremendously.

I have never been much for organized tours, and especially those which seemed to incorporate the local population as colorful backdrop to the tourist experience. I had also never understood the mentality of Americans who insisted on eating at Mickey D’s or associating only with other Americans while they were abroad. Why not just stay home?

Living in Helsinki

While in Helsinki, I found myself fully immersed in daily life, which meant learning to navigate the city on my own. As I have absolutely no sense of direction, I was lost nearly every day of my visit. However, invariably, someone would see the confused-looking black woman puzzling over a map and politely inquire “Could I help you find something?” My guides ranged from a very distinguished looking lady in her 60s to a teen with spiked bright red and purple hair to a heavily tattooed man In his late 30s, all of whom spoke good to excellent English, and each of whom smiled broadly in response to my declaration of “Kiitos!” (Thank you.)

Grocery shopping was also an adventure, as I soon learned to choose foods I recognized, either fresh fruits and vegetables, or clearly labeled meats and familiar brands, a surprising number of which had made the transatlantic journey to Helsinki, even if the labels were translated into words I didn’t understand. I soon surmised that this must be what illiteracy is like.

The summer school staff was also extremely friendly and helpful and the university facilities were excellent. Each summer school participant received a library account, discounted meals at various university cafeterias, computer privileges and a 200 page photocopy allowance. The summer school staff also provided a great deal of practical advice, such as recommending the purchase of transit cards for unlimited rides for the duration of our program.

The transit cards proved to be especially useful for those of us staying in Pihlajamäki, as the per ride fares would have been much more expensive over the course of the program. The transit cards provided the bonus of being valid to cover the fare for the ferry to the world-famous fortress on Suomenlinna Island. The students in the program were encouraged to explore Helsinki on our own, and even to take excursions to Tallinn and Stockholm, each of which was only a ferry ride away. Unfortunately, my budget did not allow for these excursions.

Helsinki Summer School Activities

The entire Helsinki Summer School program was a rich and varied buffet. Rather than being chained to a desk in an endless maze of windowless cubicles, or trapped in regimented rows with stacks of papers and books and forced to endure endless droning lectures, our days were filled with interactive presentations and discussions, and punctuated by field trips in and around Helsinki, guided by subject matter experts and knowledgeable locals.

The mishap described at the beginning of this essay occurred during an all-day class excursion to a development in progress on the outskirts of Helsinki. The purpose was to observe the guiding principles of urban development in Finland in action. This venture, along with other out of class trips, was a vital element of our learning. Seeing the developments and neighborhoods for ourselves provided experiences which would have been impossible to duplicate strictly within the classroom.

The day had begun, as all class days did, with the daily bus ride from my flat in Pihlajamäki to the Central Railway Station, smack in the midst of downtown Helsinki. Fortunately, I had met up with Stefanie, one of my classmates who was also staying at Pihlajamäki, on the trip into town, because I had no clue how to navigate from the railway station to the bus station where we were to meet our fellow classmates for the longer trip out to Espoo. With her guidance, I made it to the rendezvous point in good time.

After the bus ride, we embarked on foot from the highway across still undeveloped fields. After some hours of walking, we made our way to a mixed income development, where social (subsidized) housing was seamlessly integrated with much more affluent developments. There we enjoyed our open air picnic, then more walking, another break for coffee and cake, with a presentation on a particular social housing project by a resident. More walking, then a ride on the subway back into downtown, with an invitation to meet again in two hours at our instructor’s flat, which was located close to the tram line 15 minutes or so from the railway station.

Nearly everyone wanted a shower after what had been an enjoyable, but long and physically strenuous day. However, while the majority of our classmates were staying in the hostel located downtown, those of us assigned to Pihlajamäki were a half-hour bus ride away. Still, I needed a shower, so, along with Valdet, a neighbor from a flat down the hall, I made the trip back to Pihlajamäki.

“I’ll come by to pick you up in 15 minutes,” Valdet declared as we left the elevator on the hallway leading to our respective flats.

“FIFTEEN MINUTES?! “ I protested. “No way!”

“Yes,” he insisted. “We have to. It will take us close to an hour to get to Kaisa’s place and I don’t want to be late.” He was right, especially given the fact that neither of us had actually been to Kaisa’s place, and were therefore not entirely sure how to find it. But I had never showered and changed in fifteen minutes in my life, and especially not after having had such an arduous day. I wanted a nice, long soak in a hot bath. It was not to be. Twenty minutes later (and I was grateful for the five minute slack), there was a knock on my door, and Valdet and I were off.

Social Life

At Kaisa’s place, we were entertained by her adorable blond toddler and welcomed by her gracious husband, who seemed to take having more than twenty visitors in their comfortable (but not especially large) flat absolutely in stride. Two of our Italian classmates, Johanna and Graziana, treated our palates by preparing a variety of delicious authentic pastas and sauces, with assistance from other classmates recruited into the enterprise and accompanied by good wine and beer.

On the last day of class, again invited to Kaisa’s place, we surprised her with a T-shirt imprinted with a class photo and featuring the flags of all the participants in the class. In turn, Kaisa treated us to flutes of Cristal.

|

| Kaisa Schmidt-Thome, the course instructor, wearing the T-shirt we gave her on the last day of class. |

That night, all the summer school participants were invited to a farewell party at The Club, a downtown Helsinki nightspot. Again, my first instinct was to pass, especially since I could use the time to pack, and then to sleep before the long return trip. But I was persuaded to begin packing early and sleep on the plane.

I made my appearance at The Club at about 10:30 p.m. local time. The party was just getting underway. The venue was packed and the music was loud. Still, I heard my name even before I stepped inside. Mihai was standing just outside the door.

“You found it!” he said with a teasing smile. By this time my misadventures with finding my way around Helsinki were infamous.

“I did,” I replied with a grin.

Inside, the packed room, an open seat miraculously appeared and I was invited to sit with a group of my classmates and Kaisa, our class instructor.

“I’m so glad you decided to come!” Kaisa declared. I was glad, too.

Hearing the assorted charming accents, each clamoring to be heard over the pounding bass, were like music for me. Although nearly everyone spoke English (it was the only language we all had in common) I was one of the few persons present for whom it was a native language.